Understanding the Procurement Process: Steps, Owners, and Best Practices

The procurement process is the workflow that turns a business need into an approved purchase, a received good or service, and a paid invoice. When it works well, teams get what they need quickly, finance maintains control over spend, and suppliers are paid accurately and on time. When it doesn’t, organizations see delays, budget overruns, invoice exceptions, and frustrated stakeholders.

This guide breaks down the procurement process step by step, with a practical focus on who owns each stage, where delays commonly occur, and how organizations can improve speed and visibility without sacrificing control. Whether you’re formalizing procurement for the first time or refining an existing process, understanding how these steps fit together is essential to running procurement efficiently at scale.

Procurement Basics

Procurement is the rules and workflow that keep buying consistent. It determines when a request needs approval, when a PO is required, how suppliers are chosen, and how purchases are tracked through to payment. Without a clear procurement process, teams buy in inconsistent ways, invoices arrive without context, and finance spends time resolving exceptions instead of controlling spend.

Types of procurement

Not every purchase moves through procurement in the same way. The category of spend affects how sourcing is handled, how receiving works, and how invoices are reviewed.

- Direct procurement covers materials or components used to produce what an organization sells. Because delays or quality issues can disrupt operations, these purchases often require tighter supplier coordination and delivery tracking.

- Indirect procurement includes the goods and services that support day-to-day operations, such as office supplies, software, and facilities. Here, speed, policy compliance, and consistent approval rules tend to matter most.

- Services procurement applies to external labor or expertise, such as consultants or IT support. In these cases, “receiving” is typically tied to milestone completion or time approval rather than physical delivery.

While direct and indirect purchases follow the same core procurement process, the controls and handoffs vary by category, particularly around sourcing rigor, receiving, and invoice validation

The procurement process (9 steps)

Every company tweaks procurement based on what they buy and how regulated they are. But the core is pretty consistent. The point is to make purchases easy to approve, easy to track, and easy to match when the invoice shows up.

1) Identify the need

A team flags a purchase and clarifies what problem they’re solving (replacement, new project, recurring need). Watch for “urgent” requests that are really duplicates of something already stocked or already covered by an existing contract.

2) Define requirements

The request gets specific: what is being bought, when it’s needed, and what constraints apply (specs, budget, compliance). What good looks like: anyone outside the requestor’s team can read the requirements and understand exactly what “done” means.

3) Submit the request

The request is entered in a consistent way so it can be routed, approved, and tracked without follow-up emails. Why it matters: sloppy intake is the first cause of delays—missing owner, missing vendor, missing timeline.

4) Source suppliers

Procurement identifies suppliers who can meet the requirement, starting with preferred options and expanding as needed. Decision point: if the supplier is new or the category is sensitive, this is where additional checks usually get triggered.

5) Request quotes or proposals (as needed)

For higher-value or higher-risk purchases, suppliers provide quotes or proposals so the organization can compare options. What to watch for: suppliers quoting different scopes—if inputs aren’t consistent, evaluation turns into guesswork.

6) Evaluate and select

The supplier is chosen based on the criteria that matter for the purchase: price, quality, delivery, terms, and risk. What good looks like: a short selection rationale that someone else could defend later without re-litigating the decision.

7) Negotiate terms and confirm pricing

Final terms are agreed—what’s included, what it costs, timelines, and what happens if something changes. Common failure: the important details stay in email threads instead of being captured in the PO/contract language.

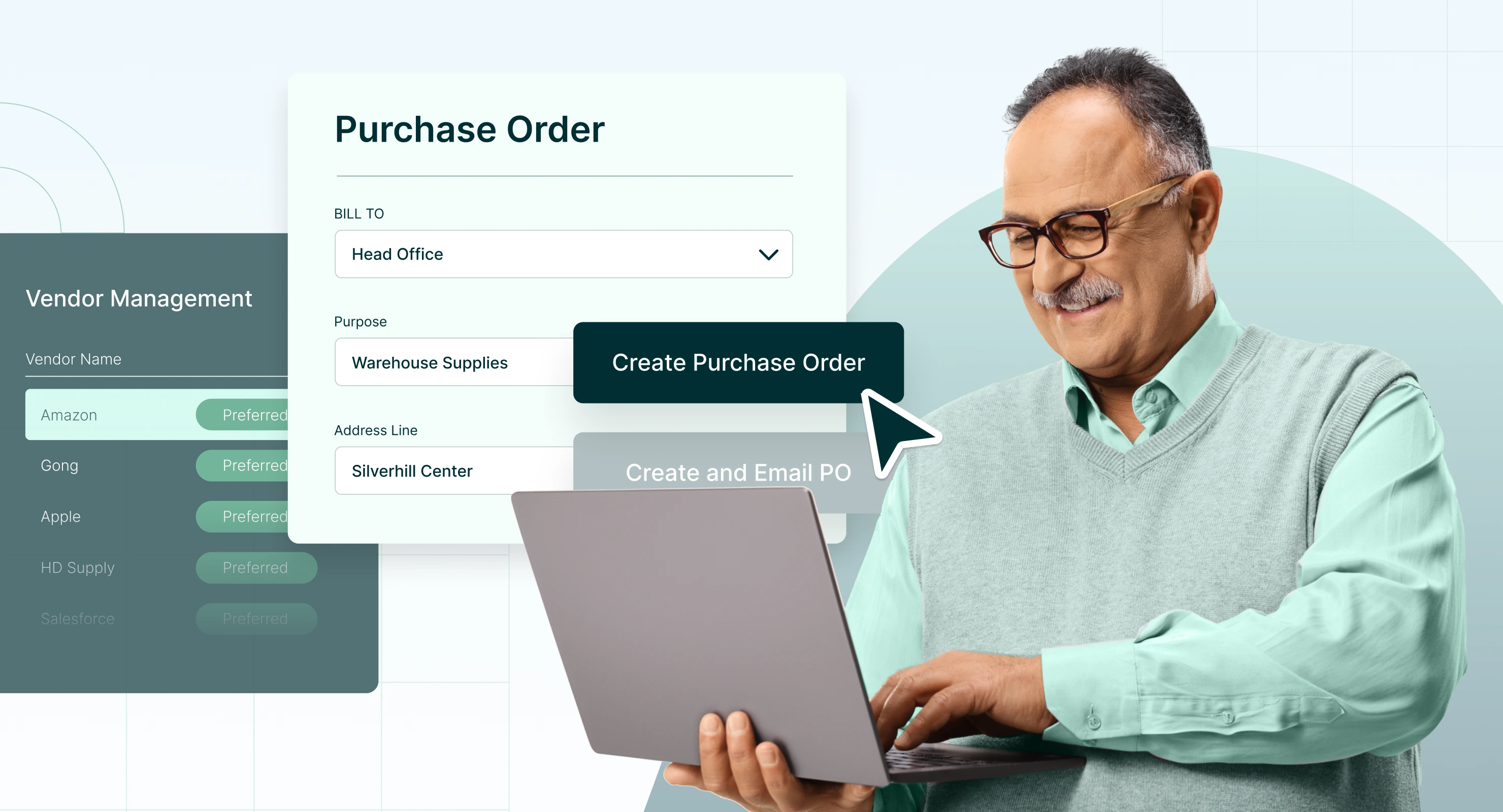

8) Create and approve the purchase order (PO)

A PO is issued with enough detail to guide fulfillment and support matching later (scope, quantities or service period, pricing, coding). Why it matters: a vague PO is how invoice exceptions get created before the invoice even arrives.

9) Receive and verify, then process payment

Delivery is confirmed (or services are signed off), invoices are matched to what was ordered and received, and exceptions are resolved before payment is released. Watch for: unclear service “receiving”—if nobody owns sign-off, payment stalls and disputes drag on.

How long is the procurement process

There isn’t one standard timeline. How long procurement takes depends less on “procurement” itself and more on what’s being bought and how much risk is involved.

Repeat purchases from an approved supplier often move quickly, especially when requirements are clear and approvals are straightforward.

New vendors or new categories usually take longer because onboarding, reviews, and approvals add steps.

Competitive sourcing or complex services can stretch timelines further, driven by scope definition, comparisons, and negotiation.

In practice, a large portion of overall cycle time shows up in the purchasing process, once a request moves out of approval and into execution. For many teams, the biggest controllable delay sits in purchase order cycle time—how long it takes to move from a request to an approved PO.

How to measure whether your procurement process is working

Savings alone won’t tell you where the process is breaking. If the goal is to improve how work actually flows, you need metrics that point to speed, control, and cleanup effort.

The most useful signals tend to be:

Cycle time: how long it takes to move from request to approved PO, and from request to receipt

Exception rate: how often invoices can’t be processed cleanly because something is missing or doesn’t match

Spend under management: how much total spend flows through defined approvals and policies

On-time delivery: whether suppliers are consistently meeting agreed timelines

Internal satisfaction: whether teams can get what they need without workarounds

Many of these indicators roll up into broader spend management, which focuses on visibility, control, and consistency across purchasing and payment. As teams mature, looking at spend analysis helps identify where delays, exceptions, or policy gaps tend to repeat.

Compliance and risk checks (where they belong in the process)

Compliance isn’t a separate phase. It shows up at a few fixed points in the procurement workflow. Miss those points, and the problems surface later as delays, exceptions, or payment issues.

When a supplier is first selected, basic eligibility is established. This is where vendor setup details are collected and verified: legal entity information, tax forms, payment details, and any category-specific requirements, such as insurance or security reviews. Skipping this step results in vendors being approved for work but blocked from payment.

During purchase approval, policy and risk thresholds are enforced. This is where spend owners are confirmed, approval levels are applied, and requirements like competitive quotes or preferred supplier use are triggered. If these rules aren’t clear or consistent, approvals turn into negotiation and purchases start bypassing the process.

At PO creation, risk shows up in the details. Scope, pricing, service periods, and terms need to be specific enough to support receiving and invoice matching later. Vague or incomplete POs are one of the most common sources of downstream cleanup.

Finally, at receiving and invoice review, earlier gaps become visible. Invoices are matched to what was ordered and received, and exceptions—price variances, missing receipts, unclear scope—are routed back to the right owner. When upstream checks were done properly, this step is routine. When they weren’t, it becomes investigative work.

This is what spend controls look like in practice: the same checks, at the same points in the process, so issues surface early instead of landing in AP after the fact.

Sustainability in the procurement process

Sustainability is handled at the same points where procurement decisions are already being made. It comes into play during sourcing, when suppliers are compared on more than price alone. It’s reinforced during approvals, where certain categories or spend levels trigger additional requirements. It becomes enforceable at PO and contract creation, when expectations are written into scope or terms. And it shows up again during supplier review, when performance is evaluated and renewal decisions are made.

In practice, sustainability follows the same path as cost, quality, and delivery; it moves through the process where spend management benefits are realized through documented decisions and consistent controls.

What’s changing in procurement in 2026

Procurement teams aren’t short on priorities. They’re short on time.

Most of the effort right now is going into the same three pressure points: getting purchases moving faster, reducing the mess that shows up at invoice time, and making sure decisions are defensible when finance asks what happened.

You can see it in where AI is actually being used. It’s not “AI in procurement” as a concept it is actually being deployed. In the next year, 50% of organizations use AI to support supplier contract negotiations. What used to take teams hours can be managed in minutes through smart contract management.

Upstream is getting tightened too, because the requisition stage is still where processes fall apart. The issue usually isn’t that people refuse to follow the process. It’s that the process asks for too little information up front, ownership is unclear, and approvals turn into back-and-forth. Teams are getting stricter about what has to be in a request, who owns it, and where it should route. When intake is clean, everything downstream gets easier.

Analytics is being used in a more blunt way than most “procurement analytics” content admits. It’s not about more dashboards. It’s about identifying repeat offenders: which categories create the most exceptions, which suppliers create the most rework, where approvals stall, where invoices fail to match, and why. When you fix those few choke points, cycle time drops without adding headcount.

Resilience is still on the table, but it’s not a blanket program anymore. Teams are picking their spots—categories where a disruption actually stops operations, single-source suppliers, long lead times, volatile pricing—and building backups only where the business would feel it.

ESG and due diligence work hasn’t gone away either, but it’s also not as simple as “do more reporting.” Some requirements are tightening; others are being simplified. In practice, procurement still gets asked for supplier data and traceability because customers, boards, and larger partners want it. The difference is that teams are trying to make that information part of the workflow instead of a separate reporting exercise.

The constant constraint is still talent. Most teams can’t hire their way out of complexity. According to Deloitte’s 2025 Chief Procurement survey the play in 2026 is straightforward: standardize the steps, automate what repeats, and save human time for the moments that actually require judgment—supplier tradeoffs, negotiation, and risk calls.

Procurement best practices (that actually reduce cycle time and exceptions)

Tighten intake

Require the info that always gets chased later: what’s being bought, who owns the budget, when it’s needed, and the supplier (if known). Tools like AI intake for orders can help capture and route requests consistently so approvals don’t turn into a thread of follow-up questions.

Make approvals predictable

Use clear thresholds and routing. People shouldn’t have to guess who signs what—or re-request approval because the wrong person was tagged.

Write POs so they’re matchable

Scope and pricing should be clear enough that invoice review is routine. For services, include the service period or deliverables so “receiving” isn’t ambiguous.

Treat exceptions like a signal

If the same issues keep showing up (missing PO, price variance, no receipt), fix the upstream step that’s causing it instead of letting AP clean it up forever.

Review suppliers using a short set of facts

On-time delivery, issue rate, responsiveness, and exception frequency will tell you more than a long scorecard nobody uses.

Conclusion

If you made it this far, you’ve got the full picture: procurement isn’t one big decision, it’s a chain of small ones that need to connect. The work is mostly making sure the next step has what it needs—enough detail in the request, a clear path through approvals, and a PO that reflects the real scope so receiving and invoice matching don’t turn into detective work.

If you’re looking for a practical place to start, pick one spot that causes the most back-and-forth in your org and clean that up first. For most teams, that’s intake and PO quality. Once those two are consistent, the rest of the process gets easier to run because fewer issues get pushed downstream.

Preview AI Intake for Orders

Take the product tour to see how the new intake experience works.